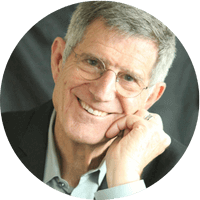

Kendall Haven

Master Storyteller

Haven is the founder of the field of Neural Story Science and worked with DoD DARPA to determine the cognitive neurology of how stories exert influence. He serves as a story consultant to departments in various governmental science agencies (Navy, DoD, EPA, NASA, NOAA, and NPS) as well as for numerous corporations, nonprofits, international governments, and educational organizations and was selected as a featured presenter at multiple Aspen Ideas Fests. Haven has won 20 major awards for his writing and performance storytelling.

Key takeaways:

- Kendall Haven’s Background: A master storyteller who performed for over seven million people, founded story science, led research for the National Storytelling Association, and is a distinguished scholar at Stanford and Johns Hopkins, with 34 books and 20 awards on storytelling.

- Neuroscience of Story: Haven’s 40 years of research, including fMRI and EEG studies, show the human brain is hardwired to process information in story terms via a neural story net, making sense of the world subconsciously before conscious awareness.

- Story Elements: Eight core elements drive story comprehension: character, character traits, goal, motive, problems, conflicts, risk, and danger, with stories revolving around characters struggling to achieve goals against obstacles.

- Make Sense Mandate: Humans automatically interpret information to make sense using story structures, as demonstrated by Haven’s conversational examples (e.g., “Where’s John?” and “I saw a green VW”), where listeners infer connections subconsciously.

- Educational Impact: Teaching story elements consciously enhances learning across subjects, with research showing improved math scores and problem-solving skills when children master story structure, as seen in Haven’s and Tales Toolkit’s studies.

- Storytelling Games: Haven suggests two games for classrooms: “Big Three Plus” (students create character, goal, and conflicts, then expand with motives) and the “Why Game” (asking “why” to build backstory and motives), fostering creative and critical thinking.

- Importance of Storytelling: Storytelling is central to human learning, not a supplementary activity, as it develops cognitive control over story elements, essential for functioning and resilience, especially in modern contexts where play and storytelling are reduced.

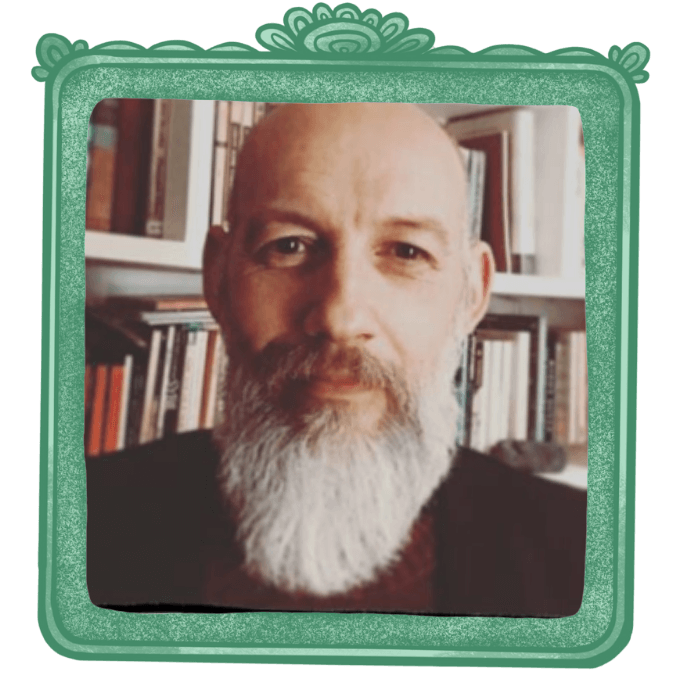

Related Webinars

We'd love your feedback!

Did you love it or hate it? And what ideas have you got for upcoming webinars - big names you'd love to see or topics you'd like covered?

.avif)